"Servant of the People or Master of the Law? Why the Supreme Court Won’t Let MLAs Hide Behind 'Private Citizen' Status"

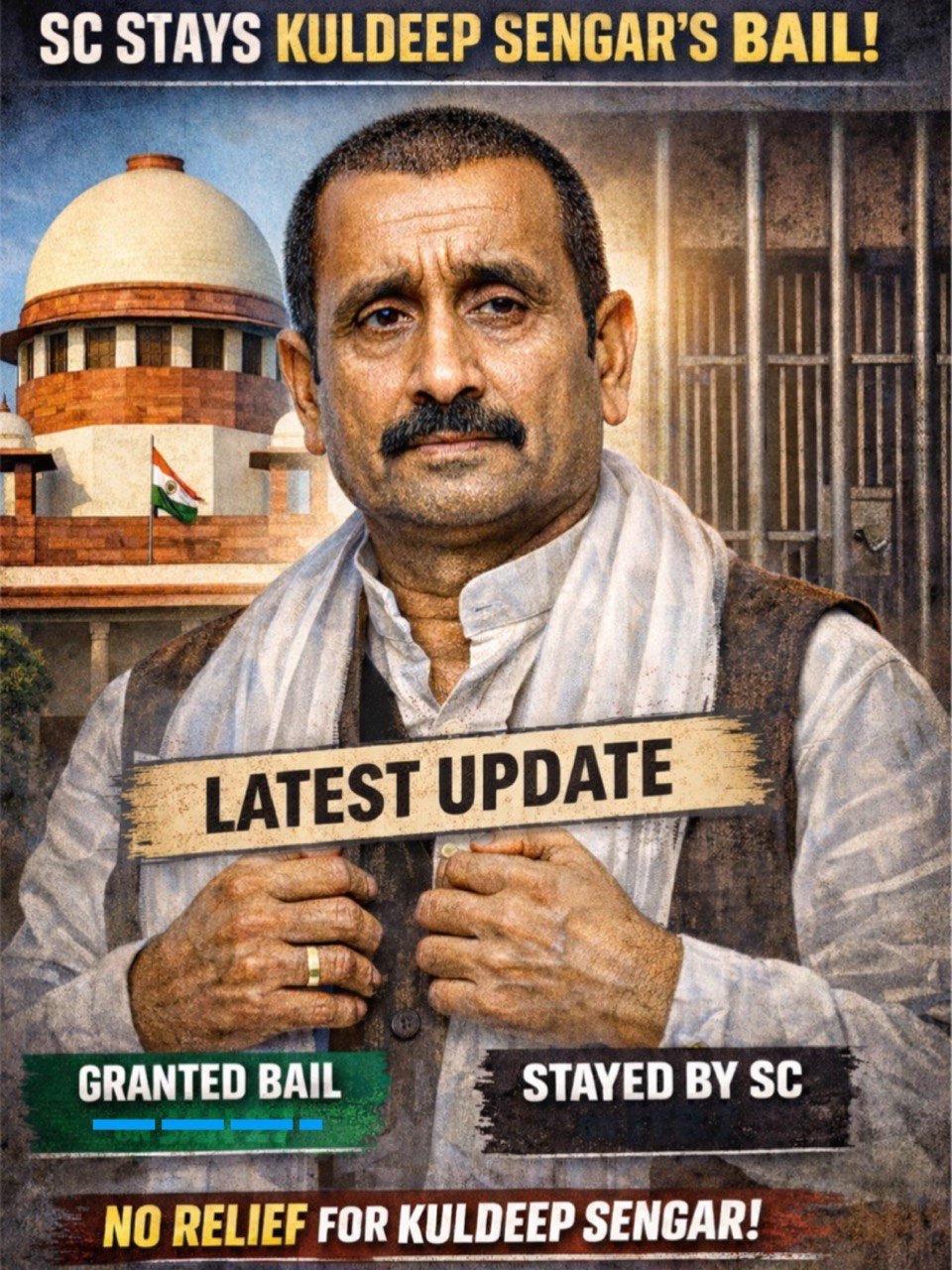

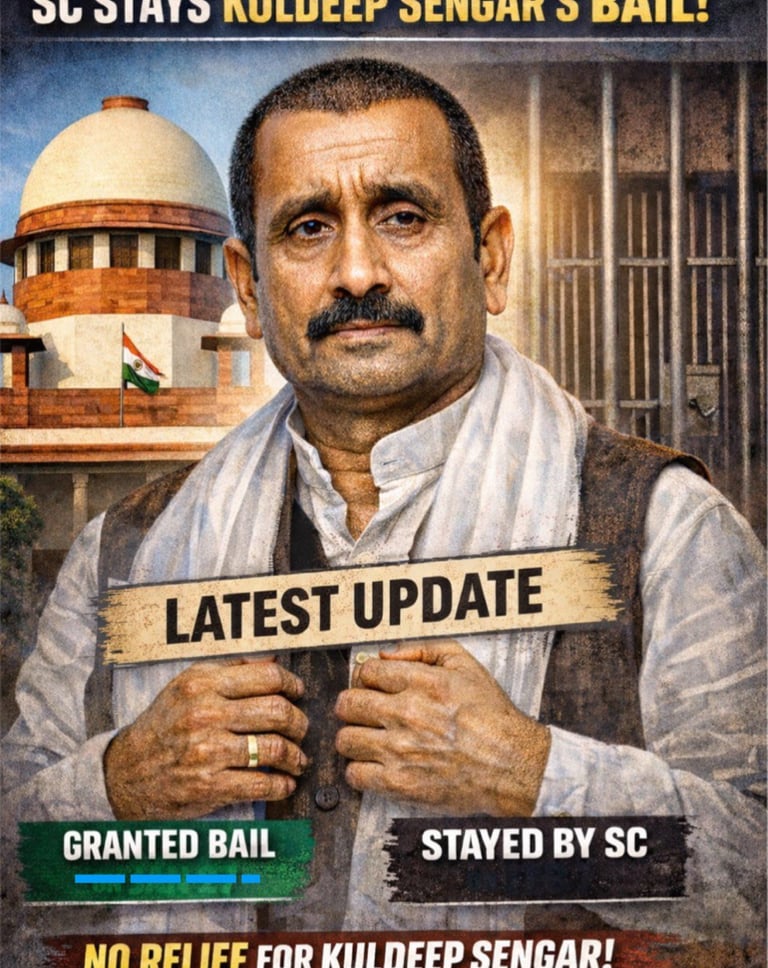

On Monday, the Supreme Court stayed a Delhi High Court order that had suspended the sentence of expelled BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar

LAW

“We are answerable to the child who was only 15 years old when this gruesome crime happened to her... If a person is in a dominant position over the victim, the crime should be interpreted as an ‘aggravated sexual assault’.”— Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, Supreme Court of India (Dec 29, 2025)

It is a rare day in legal history when the definition of a single word—"Public Servant"—threatens to unravel the justice delivered in one of India’s most horrific crimes.

On Monday, the Supreme Court stayed a Delhi High Court order that had suspended the sentence of expelled BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar. For the survivor of the 2017 Unnao rape case, this was a moment of breathless anxiety. For legal scholars, it was the opening of a Pandora’s box concerning statutory interpretation, power dynamics, and the "technical" loopholes that powerful men exploit.

The Delhi High Court’s logic for granting bail was mathematically precise but morally jarring: it hinged on the argument that an MLA is not technically a "public servant" under the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The Supreme Court, led by CJI Surya Kant, has now pressed the pause button, flagging "substantial questions of law".

Here is the deep legal dive into how a corruption-law precedent from 1984 almost allowed a convicted rapist to walk free in 2025, and why the Supreme Court had to intervene.

The Big Picture: Why Was Bail Granted?

To understand the Supreme Court’s stay, we must first dissect the High Court’s controversial relief. The Delhi High Court did not declare Sengar innocent. Instead, it suspended his sentence pending appeal.

The logic was a two-step legal maneuver:

The Charge Downgrade: Sengar was convicted under Section 5(c) of the POCSO Act (Aggravated Penetrative Sexual Assault by a Public Servant). The High Court prima facie observed that an MLA is not a "public servant" under the strict definition of the IPC. Therefore, Section 5(c) (which carries a minimum 10-year sentence under the 2012 Act) should not apply. The charge, in the HC's view, drops to Section 3 (Penetrative Sexual Assault).

The Sentencing Math: Under the 2012 POCSO Act (applicable to the 2017 crime), Section 3 carried a minimum sentence of 7 years. Sengar has already served roughly 7.5 years.

HC's Conclusion: Since he has served more than the minimum sentence for the "correct" charge (Section 3), he is entitled to bail during the years-long appeal process.

The "3-Year Gap": How the Legal Label Changed Sengar's Bail Prospects

The Legal Loophole: The Antulay Paradox

The High Court’s reasoning rests on a "hyper-technical" interpretation of the law that has fascinated and frustrated lawyers for decades.

Section 5(c) of POCSO punishes "sexual assault by a public servant." However, POCSO does not define "public servant" itself; it borrows the definition from Section 21 of the IPC.

Here lies the twist. In the landmark case of R.S. Nayak v. A.R. Antulay (1984), a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court held that an MLA is not a "public servant" under Section 21 of the IPC because they are not "in the pay of the government" (they receive an honorarium, not a salary, technically).

The Fascinating Angle: The Antulay ruling was originally a victory for civil liberties—it was designed to protect politicians from being easily prosecuted by the state for corruption without proper sanction.

Then (1984): The definition was narrowed to protect an MLA from executive overreach.

Now (2025): That same narrow definition is being weaponised to protect an MLA from aggravated liability for child rape.

The High Court essentially ruled that while Sengar might be a "public servant" under the Prevention of Corruption Act (which was later amended to explicitly include MLAs), the IPC/POCSO definition has not been updated to include them. Thus, legally, Sengar was just a "private citizen" when he committed the crime, removing the "aggravated" label.

The Supreme Court Intervenes: The 'Dominant Position' Doctrine

The CBI, represented by Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, attacked this "mechanical" interpretation. Their argument before the Supreme Court introduces a critical legal evolution: The Test of Dominance.

The Solicitor General argued that POCSO is a "special welfare legislation." Unlike the IPC or Corruption Acts, which protect the state or property, POCSO protects a child’s body and dignity. Therefore, definitions in POCSO must be read "purposively" (to achieve the law's purpose) rather than "literally".

Key Arguments by the CBI:

Section 5 is about Power, not Paychecks: The intent of Section 5(c) is to punish those who abuse authority. Whether an MLA gets a "salary" or "allowance" is irrelevant to a 15-year-old victim. The MLA holds a "Dominant Position" over the victim's family, especially in a rural constituency.

The Aggravation Factor: If a police constable (who is a public servant) commits rape, it is aggravated. If a powerful MLA (who commands the constable) does the same, how can it be a lesser offense? This creates an absurdity in the law.

Substantial Questions of Law: The SC bench noted that whether the Antulay precedent (based on corruption) applies to heinous crimes under POCSO is a "substantial question of law" that needs to be settled by the top court, not assumed by the High Court.

The Law Point: Section 389 CrPC vs. Presumption of Innocence

Why is this stay so significant legally?

Usually, under Section 389 of the CrPC (now Section 430 of the BNSS), appellate courts are generous with suspending sentences if the appeal won't be heard for years. The logic is: "If we don't grant bail now, and he is acquitted 10 years later, he would have served a sentence for a crime he didn't commit."

However, for heinous crimes, the Supreme Court has carved out exceptions (e.g., Omprakash Sahni v. Jai Shankar Chaudhary). The presumption of innocence is gone post-conviction. The Court must look at the "gravity of the offence."

By staying the order, the SC has signalled that the "gravity" of an MLA abusing his position outweighs the "liberty" interest of the convict, even if there is a technical debate about his job title.

Why This Matters: The 'Constitutional Fiduciary' Angle

This case presents a unique and fascinating intersection of Constitutional Law and Criminal Law: the Theory of the Constitutional Fiduciary.

In modern legal theory, elected representatives are not just "employees" of the state (which the Antulay test focused on); they are "fiduciaries" holding a trust for the people.

The Argument for the Future: If the Supreme Court eventually rules on this, they may expand the definition of "Public Servant" in POCSO to include anyone holding "Constitutional Trust."

The Danger: If the High Court's view stands, it essentially grants a form of "Sovereign Immunity" to MPs and MLAs. It would mean that a school teacher (public servant) faces life imprisonment for the same act that an MLA might only face 7 years for, simply because the MLA's paycheck structure is different.

What Happens Next?

Kuldeep Sengar remains in Tihar Jail. Not just because of this stay, but because he is serving a concurrent 10-year sentence for the custodial death of the rape survivor’s father a grim reminder of the "Dominant Position" he held.

The Supreme Court has issued notice and will now decide a question that will echo through Indian criminal law: Is an MLA a servant of the public, or a master above the law?

For now, the technicality has failed. The "spirit of the law" stands guard over the survivor.

Views are personal.